An Evidence-Based Analysis

The claim that banks create money “out of nothing” when they issue loans is fundamentally correct, though the phrase requires important nuance. This understanding, long dismissed as heterodox, has been formally acknowledged by major central banks and is now supported by rigorous empirical evidence and economic theory.

The Core Mechanism: How Banks Actually Create Money

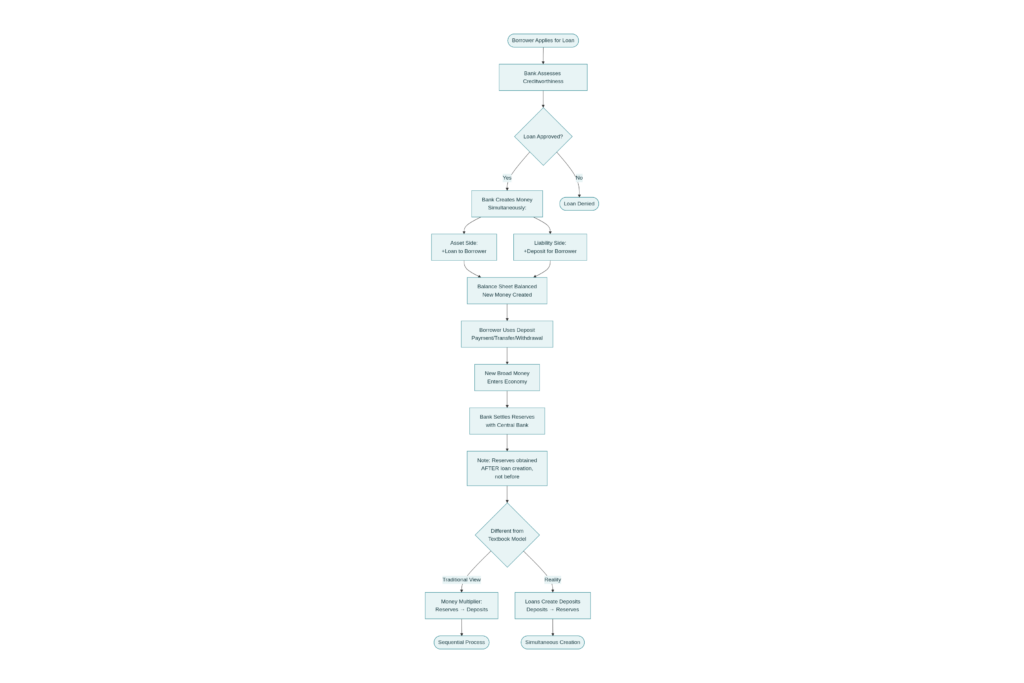

When a bank makes a loan, it performs a simultaneous double-entry accounting action: it creates both a loan asset on its balance sheet and a corresponding deposit liability in the borrower’s account. This is not a transfer of pre-existing funds. The deposit which becomes purchasing power in the economy did not exist before the bank created it. The borrower now possesses money (in their bank account) that was created by the act of lending itself.bankofengland

This differs fundamentally from how most people conceptualize banking. The intuitive assumption that banks collect deposits from savers and lend them to borrowers is incorrect. As the Bank of England officially stated: “The principal way is through commercial banks making loans. Whenever a bank makes a loan, it creates a deposit in the borrower’s bank account, thereby creating new money.” The causality runs from loans to deposits, not deposits to loans.bankofengland

When the borrower spends that newly created deposit say, purchasing a car the bank enters the transaction in its settlement account with other banks. The central bank then supplies the reserves needed to settle this payment through the interbank system, accommodating the reserve requirement after the fact. The central bank does not constrain lending by limiting reserves; rather, it manages the price of reserves (the interest rate) and supplies them on demand.hks.harvard

The Most Downloaded Paper: Empirical Validation

The audio’s reference to the “most downloaded Elsevier paper” appears to cite Richard Werner’s 2014 study, “Can banks individually create money out of nothing?” This was the first empirical test of competing banking theories. Werner’s methodology was direct: he borrowed money from a cooperating bank while monitoring its internal records to determine whether the bank transferred funds from other accounts or created new deposits. His finding was unequivocal: “banks individually create money out of nothing. The money supply is created as ‘fairy dust’ produced by the banks individually, ‘out of thin air.’”econpapers.repec

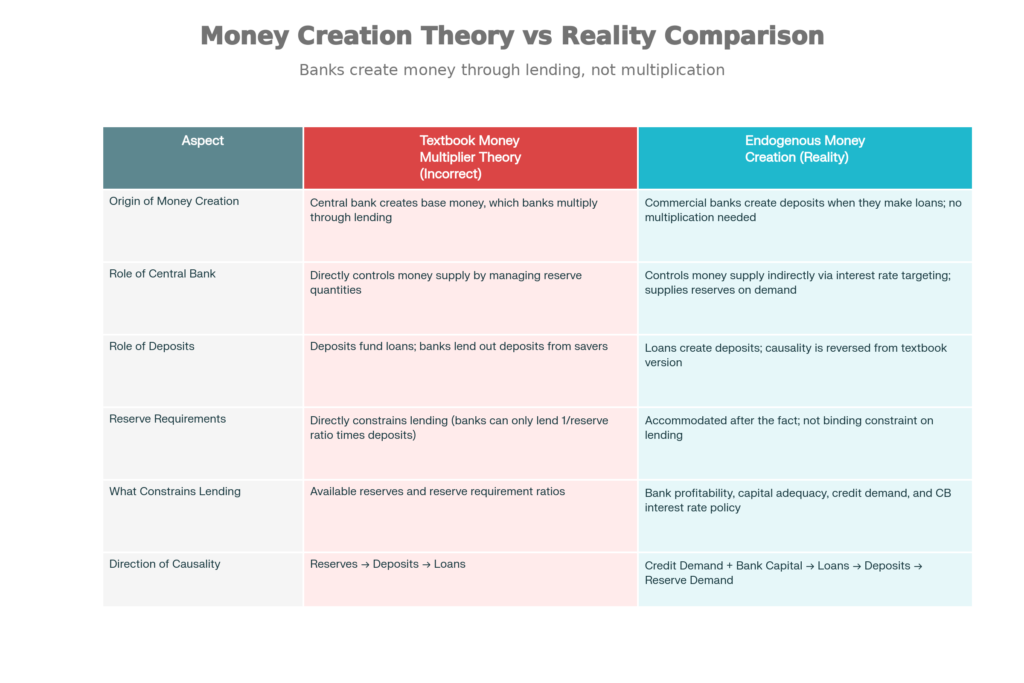

This empirical verification, combined with decades of post-Keynesian monetary theory and modern central bank acknowledgments, has resolved what was once a contentious debate. The textbook money multiplier mechanism where central bank reserves are “multiplied up” through sequential lending rounds is now recognized by central banks themselves as an outdated and misleading model.

Central Banks Have Acknowledged the Reality

In March 2014, the Bank of England published an article titled “Money creation in the modern economy” dispelling common misconceptions. The article explicitly states that banks do not act “simply as intermediaries, lending out deposits that savers place with them” and nor do they “multiply up” central bank money. The act of lending creates deposits; reserves follow afterward, accommodated by the central bank.bankofengland

The Federal Reserve has reinforced this understanding. In 2021, the Fed launched educational resources recommending that instructors “avoid relying on the money multiplier concept” and explicitly acknowledged that commercial banks, not the Federal Reserve, are the creators of broad money.wikipedia

What “Out of Nothing” Really Means

The phrase “out of nothing” requires precision. Banks don’t create value ex nihilo; they create liabilities backed by their expectation of receiving future cash flows from the borrower. The money created is purchasing power the ability to buy goods and services derived from the bank’s intermediation function and its ability to assess credit risk. The borrower promises to repay the loan from future earnings, which gives the deposit its value.

In accounting terms, “nothing” means no pre-existing reserves or deposits were transferred. In economic terms, the creation is constrained by three critical factors:

- Profitability: Banks will not make loans they expect to be unprofitable after accounting for administration costs, credit risk, and required capital buffers.

- Capital adequacy requirements: Banks must hold approximately 8-10% of risk-weighted assets in equity capital. This is a hard constraint on growth.

- Credit demand and creditworthiness: Banks can only lend to borrowers willing to borrow and whom they assess as creditworthy.

These constraints mean that banking systems do not infinitely expand the money supply. The empirical evidence from the academic model by Heon Lee (2024) demonstrates that the money multiplier the ratio of broad money to central bank money is endogenously determined by policy rates, capital adequacy, and credit availability, not by fixed reserve ratios.arxiv

Why the Textbook Story Persists as Myth

The outdated textbook framework assumed that central banks controlled the money supply by managing reserve quantities, which banks then “multiplied” based on reserve requirements. According to this logic, if the required reserve ratio is 10%, a deposit of $100 could theoretically support $1,000 in loans.

This mechanism rarely operated as described. In reality:

- Reserve requirements were never binding constraints; banks regularly held more than required reserves.

- Central banks did not manage monetary policy by controlling reserve quantities; they managed interest rates.

- Money flows through the economy are driven by lending decisions made by banks in response to interest rates and credit opportunities, not by reserve availability.

These facts led major central banks to abandon attempts at reserve quantity control in the early 1990s, pivoting instead to interest rate targeting. Yet the money multiplier framework remained embedded in introductory economics textbooks, decades after central banks ceased using it.

The Role of Central Banks: Gatekeepers, Not Engineers

The central bank’s role is critical but indirect. It does not “create” broad money (bank deposits), which constitute approximately 97% of the money supply. Instead, it:economicshelp

- Sets the price of reserves: By setting the short-term interest rate (the federal funds rate in the US), the central bank influences banks’ lending decisions. Lower rates encourage borrowing and lending; higher rates discourage it.

- Supplies reserves elastically: When banks need reserves for settlement, the central bank provides them at the target rate. Demand for reserves adjusts to the policy rate set by the central bank.

- Controls inflation through demand management: By raising or lowering interest rates, the central bank influences credit demand and thus the pace of broad money creation, which ultimately determines inflation.

The Constraints on Bank Money Creation

While banks do create money through lending, the system has built-in stabilizers:

Interest Rate Policy: When the central bank raises rates, borrowing becomes more expensive, reducing loan demand and thus deposit creation. Conversely, lower rates stimulate lending.

Capital Requirements: Basel III and subsequent regulations require banks to hold capital proportional to risk-weighted assets. A bank with $10 billion in capital cannot indefinitely expand its loan book; capital becomes the binding constraint.

Credit Cycles: During booms, banks expand lending aggressively; during downturns, they contract. This procyclicality has macroeconomic consequences and is why regulators impose countercyclical capital buffers.

Competition and Profitability: Banks compete for creditworthy borrowers. If loan spreads compress (the difference between lending rates and cost of funding narrows), lending becomes unprofitable and slows.

Where the Audio’s Framing Falls Short

The audio correctly identifies that banks create deposits through lending but frames this as banks “borrowing from us” (borrowers). This inverts the liability relationship. When you borrow from a bank, the bank creates a deposit (an asset for you, a liability for the bank) while you incur a loan obligation (a liability for you, an asset for the bank). You are not lending to the bank; you are borrowing from it.

A more precise framing: Banks profit by creating liabilities (deposits) that serve as money, leveraging their perceived creditworthiness. Borrowers incur obligations to repay these liabilities. The central bank ensures the stability of this system by managing interest rates and standing ready to supply reserves.

Academic and Institutional Consensus

This framework is now dominant in monetary economics research. Post-Keynesian economists (heterodox school) have advanced endogenous money theories since the 1970s. Modern mainstream monetary economists, including those at central banks, have converged on this understanding. The debate has shifted from “Do banks create money?” to “What are the constraints on money creation?” and “How does the central bank best manage these constraints?”

Conclusion: True But Incomplete

Yes, banks do create money “out of nothing” in the accounting sense they create deposits without transferring pre-existing reserves. This is now acknowledged by the Bank of England, the Federal Reserve, and validated by empirical research. However, this is not sinister or unlimited. Banks are constrained by capital requirements, profitability, credit demand, and central bank interest rate policy. The creation of broad money is endogenous driven by lending decisions made by banks in response to borrower demand and policy incentives—but the pace of creation is ultimately controlled by the central bank through its influence over interest rates and inflation expectations.

The real issue is not that banks create money, but how effectively monetary and financial authorities manage the pace of creation to maintain price stability and financial system soundness. On that question, central banks have far more sophisticated tools than the textbook money multiplier model suggested.

Key Sources

Lee, H. (2024). “Money Creation and Banking: Theory and Evidence.” ArXiv. Develops a monetary-search model explaining endogenous money multiplier and empirically validates it against US data (1959-2015).arxiv

Wikipedia. “Money multiplier.” Cites Federal Reserve 2021 educational resources recommending avoidance of money multiplier concept.wikipedia

Werner, R. A. (2014). “Can banks individually create money out of nothing?” International Review of Financial Analysis, 36, 1-19. First empirical evidence of individual bank money creation.econpapers.repec

Bank of England. (2014). “Money creation in the modern economy.” Quarterly Bulletin Q1. Official central bank explanation dispelling misconceptions about money multiplier.bankofengland

Economics Help. “Banks and the Creation of Money.” Cites Bank of England explanation of bank deposits as primary component of modern money supply.economicshelp

- https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/quarterly-bulletin/2014/q1/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy

- https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/centers/mrcbg/programs/senior.fellows/2019-20%20fellows/BanksCannotLendOutReservesAug2013_%20(002).pdf

- https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:finana:v:36:y:2014:i:c:p:1-19

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money_multiplier

- http://arxiv.org/pdf/2109.15096.pdf

- https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/667/money/banks-and-the-creation-of-money/

- https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3156146

- https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-14489-0_3

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/caef3277b04585cf93886b0a8f1072ac8f58e76d

- https://www.ijsshr.in/v8i1/71.php

- http://dhs.ff.untz.ba/index.php/home/article/view/16971/1019

- https://www.mdpi.com/1911-8074/16/7/302

- https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-63967-9_6

- https://ijif.net/public/admin/uploads/sayfalar/187/article-1.pdf

- https://www.iiardjournals.org/abstract.php?j=IJBFR&pn=Credit%20Risk%20Management%20and%20Deposit%20Money%20Banks%E2%80%99%20Performance%20in%20Nigeria%20&id=4172

- https://www.mdpi.com/1911-8074/18/4/211

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00220485.2022.2075510?needAccess=true

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/1406099X.2019.1640958?needAccess=true

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10827450/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10064958/

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1702.08774.pdf

- http://www.aimspress.com/article/doi/10.3934/NAR.2024006

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/2104.00970.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eM1S6RiIJis

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endogenous_money

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1572308924000809

- http://www.thomaspalley.com/docs/articles/macro_theory/endogenous_money.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=93_Va7I7Lgg

- https://byjus.com/commerce/money-creation-by-banking-system/

- https://www.macroscan.org/fet/sep13/pdf/Loans_First.pdf

- https://study.com/academy/lesson/money-and-multiplier-effect-formula-and-reserve-ratio.html

- https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-macroeconomics/chapter/how-banks-create-money/

- https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=4282194

- https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=4866986

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/afdacfad2d1e71c3035d2c1651b0c3a734cd3682

- https://www.sciendo.com/article/10.2478/zireb-2022-0025

- https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3563326

- https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10114503/

- http://journal.fu.unsa.ba/index.php/uprava/article/view/180

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/c93f9beae9771013d53991807d936a2459e39310

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jmcb.12975

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ehr.13349

- https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2352340918314410

- https://papyrus.bib.umontreal.ca/xmlui/bitstream/1866/32063/1/qss_a_00272%20(1).pdf

- https://direct.mit.edu/qss/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/qss_c_00305/2354358/qss_c_00305.pdf

- http://arxiv.org/pdf/2102.04789.pdf

- http://arxiv.org/pdf/2311.08617.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=naW4jCel5Zs

- https://www.smithanglin.com/blog/how-does-the-federal-reserve-create-money/

- https://centralbankofindia.co.in/sites/default/files/Policy_on_Bank_Deposit.pdf

- https://fee.org/articles/how-does-the-federal-reserve-create-money/

- https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/jcfl/vol28/iss1/2/

- https://www.centralbankofindia.co.in/sites/default/files/2021-04/POLICY-ON-BANK-DEPOSITS.pdf

- https://www.sofi.com/learn/content/how-do-fed-rates-get-funded/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S105752192100079X

- https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4095335

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/c913131aaea7558ae547f32efd961099a9fd2bfc

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/2d10032c59d49700cae3fd4899f882a5f6e7b2b1

- http://www.emerald.com/jfrc/article/6/1/84-85/214225

- https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1057521914001434

- https://www.risk.net/journal-of-financial-market-infrastructures/7960622/functional-consistency-across-retail-central-bank-digital-currency-and-commercial-bank-money

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09692290.2018.1512514

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/5721430e0f257c016abfdeab2a7d8a869683cd1e

- http://www.nber.org/papers/w26663.pdf

- http://www.emerald.com/jiabr/article/15/3/422-442/1214408

- https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2405844024001622

- https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/2103/2103.01558.pdf

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/05390184221107319

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09692290.2023.2205656?needAccess=true&role=button

- http://arxiv.org/pdf/2311.01542.pdf

- https://positivemoney.org/uk/archive/qe101-part2/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/Economics/comments/yduvr6/money_creation_in_the_modern_economy_bank_of/

- https://www.truevaluemetrics.org/DBpdfs/Money/BoE-Money-in-the-Modern-Economy-An-Introduction%202014.pdf

- https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy

Leave a Reply