Your government is supposed to be your servant but without LIMITS, it quietly starts acting like your master.

Why real democracy is impossible without a constitution that keeps government on a short, legal leash.

In every democracy, there’s a simple truth that most people forget:

You don’t belong to the government. The government belongs to you on a temporary, conditional contract.

Constitutionalism is the name given to that contract. It’s the idea that government power is created by a higher law (the Constitution) and strictly limited by it, so rulers can never legally do “whatever they want”.

But here’s the twist: almost every modern state has a written constitution; far fewer actually practice constitutionalism in real life. That gap is where democracies quietly decay.

What this article will unpack

- Why the first job of a Constitution is to limit government, not to help it “do more stuff”.

- How even elected, popular leaders can turn a democracy into “minimum democracy” while keeping all the right slogans and rituals.

- Why structures (separation of powers, judicial review, federalism) protect your freedom more than any inspiring rights preamble.

- How a country can have a beautiful Constitution on paper but zero constitutionalism in practice.

- A practical, step‑by‑step playbook you can use as a citizen to defend limited government in everyday political life.

And yes, the core inspiration for this post comes from that powerful classroom analogy:

If you hire a servant at home, why on earth would you make him all‑powerful?

In a democracy, people lend power to governments temporarily, and on strict conditions.

What “Limited Government” Really Means

Most people think “limited government” means “small government” or “weak government”. That’s not quite right.

Constitutionalism defines limited government as a system where all officials are bound by a higher law that both creates and restricts their powers. The Constitution is the supreme law, and every government action must conform to it. No minister, no majority, no emergency can legally cross those red lines without breaking the constitutional order.

Key ideas behind limited government:

- Legal supremacy: The Constitution is above Parliament, Cabinet, bureaucrats everyone.

- Rule of law: Every public authority is subject to law, not personal will or political convenience.

- Institutional checks: Power is distributed and constantly watched by other organs (legislature, executive, judiciary, federal units, integrity institutions).

In short: limited government is not about a weak state; it’s about a controlled state. A powerful government is fine as long as it is caged by law.

Insight 1: The Constitution’s First Job Is To Say “No”

Most citizens instinctively think of a Constitution as something that “gives” them rights and “empowers” the government to do welfare, development, and nation‑building. That’s only half the story and not the most important half.

Modern constitutionalism grew out of centuries of abuse by kings and absolute rulers, where power was concentrated, arbitrary, and unaccountable. The entire point of a Constitution was to bind power with rules, procedures, and boundaries.

- In the United States, the framers deliberately designed a federal government with enumerated powers it only has the powers the Constitution explicitly grants it, nothing more.

- They were more worried about a powerful government that could easily abuse liberty than about a government too weak to manage crises.

- They viewed structural limits on power as an even deeper protection for liberty than the Bill of Rights itself, because structures restrict abuse in general, not just on a few listed freedoms.

Similarly, in India, constitutionalism is defined as measures that limit government power and secure fundamental human rights, with institutions like federalism, judicial review, and the amendment process all acting as brakes on arbitrary rule.

So the radical insight is this:

A good Constitution is not a “wish‑list” of what government should do. It is first a “stop‑list” of what government must never do, no matter how popular or powerful it becomes.

Insight 2: The Real Danger Isn’t Only Dictators It’s “Too Much Democracy” Without Limits

When people hear “unlimited government”, they imagine a mustache‑twirling dictator.

Reality is more subtle and more dangerous.

Constitutional scholars warn that modern states can slide from limited government to “minimum democracy”: elections happen, constitutions exist, but effective constraints on power disappear. The state grows in size and scope, yet the real ability of citizens to control it shrinks.

Research on constitutionalism shows that:

- Without robust mechanisms to limit state power, the state inevitably encroaches on private life and civic space, threatening rights and freedoms.

- Wars, emergencies, and deep socio‑economic crises are classic moments when even established democracies “suspend” constitutionalism and centralize power.

- Longer tenures and concentration of authority even at local levels like village heads correlate with higher risks of abuse and departure from democratic ideals that demand power remain under control.

The important (and uncomfortable) truth:

Elected majorities can violate rights just as efficiently as dictators. That’s why constitutionalism treats all power even “democratic” power with deep skepticism.

Insight 3: Structures Protect You More Than Slogans

People love big words: “democracy”, “rights”, “justice”, “welfare state”.

But in constitutional design, structures beat slogans every single time.

Philosophers like Montesquieu argued that liberty requires a clear separation of powers: legislative, executive, and judicial functions must be placed in different hands so each can check the others. If the same body controls law‑making, law‑execution, and law‑judging, nothing stops it from becoming tyrannical.

Across modern constitutional democracies, a few structural tools keep government limited:

- Separation of powers & checks and balances

Different branches share power, can scrutinize each other, and can block or review actions that cross legal boundaries. - Judicial review

Courts in systems like India and the US can strike down laws and executive actions that violate the Constitution or fundamental rights. - Basic structure doctrine (India)

The Supreme Court has held that certain core features supremacy of the Constitution, rule of law, separation of powers, judicial review, federalism, secularism, democracy cannot be amended away, even by Parliament using its formal amending power. - Federalism and decentralisation

Power is vertically divided between central and state (or provincial) governments, reducing the chances of a single centre capturing everything.

Constitutional scholars note that these structural restraints on power often do more to protect liberty than the list of rights itself, because they reduce the capacity of any ruler to abuse power in the first place.

So when you care about freedom, don’t just ask “What rights do I have?”

Ask: “Who can stop the government and how, exactly?”

Insight 4: A Constitution Without Constitutionalism Is An Empty Shell

Plenty of countries have impressive‑looking constitutions and zero real freedom.

Researchers call this the problem of “a constitution without constitutionalism”: the text is there, but the culture, institutions, and enforcement of limits are missing. In such states:

- The Constitution formally promises rule of law, but in practice, officials are not truly subject to it.

- Institutions that should control power (courts, watchdogs, media, integrity bodies) are captured, weakened, or ignored.

- Citizens have rights on paper but no realistic path to enforce them against the state.

Studies on the evolution of state power show multiple “layers” of restraint are needed: power must be checked by other powers, bound by law and human rights, and embedded in a culture that treats arbitrary action as illegitimate. Constitutional rules alone are not enough, because they are interpreted and enforced by political elites who often have incentives to bend or ignore them.

That’s why limited government is as much about habits and institutions as it is about articles and clauses.

Insight 5: The People’s Power Never Fully Transfers Government Is Always On Lease

The deepest insight of constitutionalism is about who truly owns power.

Constitutional theory distinguishes between:

- Constituent power – the original, sovereign power of the people to create or change a constitution.

- Constituted power – the limited, delegated powers of government institutions created by that constitution.

Once a constitution is adopted, most scholars say the people’s constituent power is not supposed to operate casually through street whims; instead, it is channelled through formal amendment procedures and democratic processes. But many modern constitutions still acknowledge that the people retain an inalienable right to alter their form of government if the system fundamentally betrays them.

In India, courts have explicitly tied constitutionalism to control over governmental power so that the democratic principles on which government rests are not destroyed. Through doctrines like basic structure, the judiciary acts as a guardian of that original democratic choice against later abuses by transient majorities.

Put simply:

You do not “give” power to the government forever. You lend it, on a renewable, reviewable lease and the Constitution is your written contract with very strict terms.

The moment people forget this and start speaking as if “the government gives us rights”, the psychological shift toward servitude has already begun.

How Democracies Actually Limit Government Power

Let’s tie this together in practical design terms. Democracies use a bundle of mechanisms to keep the state in its proper place:

- Higher‑law Constitution

The Constitution sits above ordinary laws; any inconsistent law can be nullified, especially where judicial review is entrenched. - Separation of powers & mutual veto points

Legislatures make law, executives implement, judiciaries interpret and each can slow, block, or punish abuse by the other, as envisioned by thinkers like Montesquieu. - Judicial review + basic structure (India and similar systems)

Courts can invalidate not just ordinary laws but even constitutional amendments that damage foundational principles, ensuring that no temporary majority can rewrite the entire regime for its own benefit. - Federalism and decentralisation

Vertical division of power forces negotiation and reduces the dominance of any single centre, which is a key feature of Indian constitutionalism. - Rights + remedies

Fundamental Rights combined with strong remedies (like access to higher courts) convert theoretical rights into actionable claims against the state.

The more of these layers a system has and the more they actually function in practice — the closer it gets to real constitutionalism and limited government.

What Happens When These Limits Erode

When these guardrails weaken, countries enter the danger zone often without any formal declaration that “democracy is over”.

Research across developing and transitional states shows that:

- Emergency powers and security threats are frequent justifications for bypassing normal checks, sometimes for far longer than genuinely required.

- Extending tenures or reducing accountability of local and national executives tends to increase risks of misuse and move systems away from democratic ideals of controlled power.

- Globalisation and economic pressure can push states to recentralise power, drifting from their original limited‑government designs toward managerial, centrally driven regimes.

The bitter irony is that many of these changes are sold as “reforms”, “efficiency”, or “strong leadership” which is why constitutionalism insists on process and limits, not just outcomes.

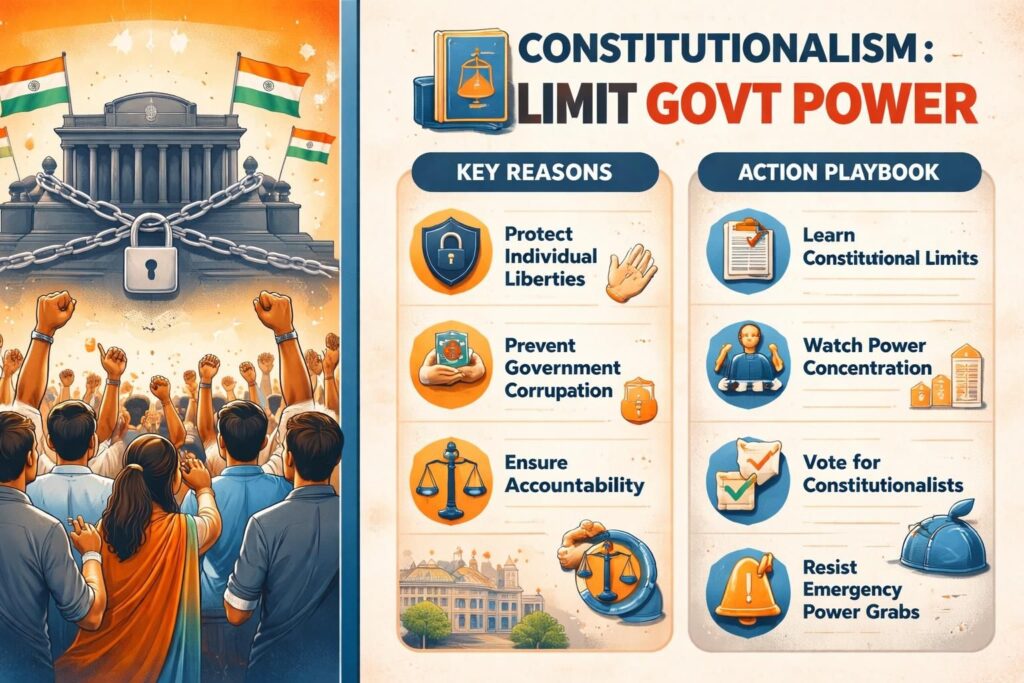

Citizen Playbook: Step‑By‑Step To Defend Limited Government

So what can an ordinary citizen actually DO with all this theory?

Here is a practical, step‑by‑step playbook to live out constitutionalism in your daily civic life:

Step 1: Learn your red lines

- Read a simple, annotated guide to your Constitution focus on:

- Fundamental Rights

- Separation of powers

- Federal provisions

- Emergency provisions

- Amendment procedure and any “basic structure” type doctrines where they exist

- You don’t need to be a lawyer. You just need to know: “What can government NEVER legally do?”

Step 2: Watch for concentration of power

Use constitutionalism as your lens when you read news:

- Are key decisions repeatedly being taken by fewer and fewer people?

- Are institutions that should check power (courts, election bodies, auditors, anti‑corruption agencies) being bypassed, packed with loyalists, or attacked?

- Are emergency powers or ordinances being used as a routine shortcut rather than an exception?

Where you see centralisation + reduced oversight, your constitutional alarm should start ringing.

Step 3: Use legal and institutional remedies

Limited government is not self‑enforcing; it needs citizens who use the system.

- Support and, where possible, participate in public‑interest litigation or constitutional challenges when laws clearly violate rights or structural principles like basic structure.

- Engage with integrity institutions (ombudsmen, human rights commissions, anti‑corruption bodies) that exist precisely to control power.

- Back independent media, civil society, and watchdog groups that monitor and expose constitutional violations.

Each time someone successfully challenges an unconstitutional action, it sends a clear signal: this society is paying attention.

Step 4: Vote like a constitutionalist, not a customer

When you vote, don’t just think, “Who will give me more schemes?”

Ask:

- Does this candidate respect separation of powers and judicial independence, or constantly attack them?

- Do they talk about process, institutions, and rule of law or only about “strong leadership” and “getting things done at any cost”?

Reward leaders who see themselves as temporary trustees under the Constitution, not as permanent saviours.

Step 5: Resist “emergency temptation”

Emergencies are real. So is the temptation to say, “Anything is justified if it solves this crisis.”

Constitutional experience shows that:

- Almost every long‑lasting democratic abuse begins as a “temporary” exception.

- War, internal conflict, and economic collapse are the classic moments when constitutionalism is suspended in the name of survival.

As a citizen:

- Support time‑bound, reviewable emergency measures with clear legal limits.

- Oppose open‑ended, vaguely defined “extraordinary powers” that lack judicial or legislative oversight.

Step 6: Build a constitutional culture around you

You don’t need a position or a title to shape political culture.

- In everyday conversations, push back gently when people say, “The government gave us these rights” remind them that rights came first; governments came later.

- Encourage friends, students, and colleagues to see government as a servant with a contract, not a feudal lord or permanent father figure.

- Share stories (not just theories) of courts, citizens, and institutions successfully checking power these narratives keep constitutional faith alive.

When enough citizens think this way, politicians are forced to adjust.

Bringing It Back To The “Servant” Analogy

Let’s return to that classroom image that sparked this whole discussion:

If you bring a servant into your home, would you hand him absolute power over you, your family, and your property?

Of course not. You would define duties, set boundaries, and keep the right to fire him.

Constitutionalism applies that simple intuition to politics.

As Lord Acton famously warned, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Separation of powers, judicial review, basic structure doctrine, and federalism are just sophisticated ways of saying: “This servant will NEVER be allowed to become our master.”

A polite, accountable, and limited government is not a sign of weakness.

It is the only kind of government that truly fits a free people.

Source Inspiration & Further Reading

This blog was inspired by popular constitutional law teaching that repeats a powerful line:

“In a democracy, governments do not grant power to people; people lend power to governments temporarily and conditionally.”

For deeper reading on this topic, explore:

- “Constitutionalism” – overview of limited government under a higher law

- iPleaders: Constitutionalism and Limited Government (Indian context, structures, fundamental rights)

- “The Form and Formation of Constitutionalism in India” – on how Indian courts balance government power and people’s rights

- Analyses of judicial review and basic structure doctrine in India

- Studies on “constitution without constitutionalism” and the dangers of emergency powers

Your Turn

Does your country really have limited government or just a fancy Constitution on paper?

What do you think: Are we treating our governments like servants on a contract, or like permanent masters?

👉 Comment below and share your view and if you want, this can be turned into a community discussion or series.

👉 Tag a friend who loves political debates but rarely talks about constitutionalism.

👉 Follow for more clear, high‑energy breakdowns of governance, democracy, and constitutional design.

- The Highest Form Of Intelligence Isn’t What You Think: Why Metacognition Beats IQ Every Time

- The Secret Wealth Game: Why You’re Poor and They’re Rich

- BROKE & CAN’T PAY YOUR LOAN? This Legal Loophole Could Save You from Financial Ruin

- The Biggest Legal Heist in History: What Central Banks REALLY Do to Your Money

- Why It’s Crucial to Restrict Government Power

Leave a Reply